|

TeKeyia and David by Sheila Pree Bright, 2007

Born

in Waycross, GA, Bright was an Army brat who spent her childhood

in Germany and criss-crossing the U.S. with her parents and three

siblings. She picked up photography during her senior year of

textile design at the University of Missouri. Nationally known

for her photographic series, Young Americans (2007),

Plastic Bodies (2003) and Suburbia (2006), her

work consistently and subtly challenges stereotypes. Shortly after

earning her M.F.A. in Photography from Georgia State University,

she received the Center Prize from the Santa Fe Center of Photography

for Suburbia. The series takes aim at the American media’s

projection of the “typical” African American community.

Brights color photographs of middle class, Atlanta homes depict

a realistic view of everyday Black life in the suburbs. She was

the first woman and person of color to win the award.

Last

year, Plastic Bodies went viral on Huffington Post.

Bright said she took the cultural icon of the Barbie doll to challenge

the notions of beauty standards and highlight their impact on

a young girl’s psyche. In this series, models and dolls

were digitally manipulated into striking images that are half-human

and half-plastic. Featured in the documentary, “Through

the Lens Darkly,” Plastic Bodies is also in the

traveling group show, Posing Beauty in

African American Culture.

Bright’s

mural, Fifteen, is an homage to the 1814 flag. Comprised

of 15 high contrast photographs, the participants are rendered

in black and white, while the flag is depicted in bold color.

On display in the museum gallery, Fifteen, also has a

public art component with companion murals at both schools.

An

unprecedented exhibition

A

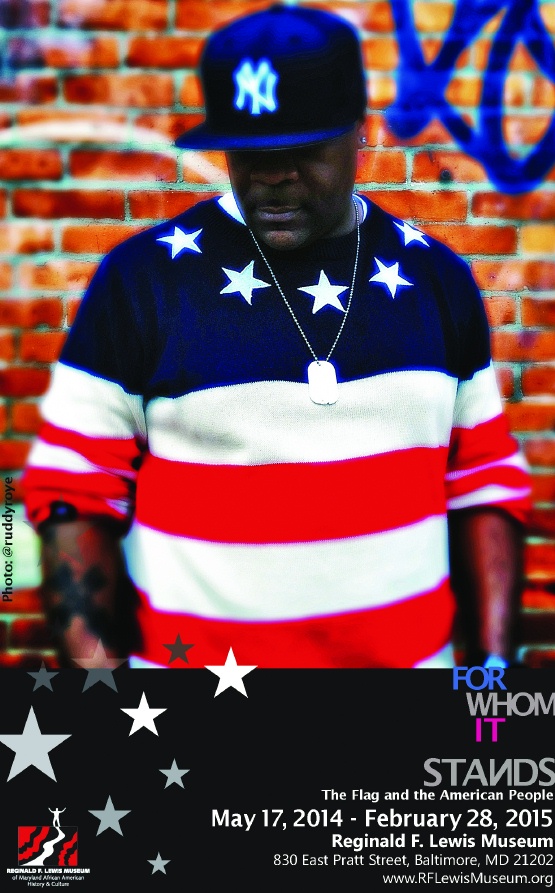

diversity of voices, young and old alike, spanning pride and protest,

fill the massive 3,200 square foot space in For Whom It Stands.

With works by major artists like Romare

Bearden, Faith Ringgold, Kerry James

Marshall and Gordon Parks, it also features lesser-known artists.

The Veteran is a mixed media work on skateboard by Rafael

Colón, a self-taught Puerto Rican artist. A Tribute to

New York City, sculpted by Israeli-American Dalya Luttwak sits

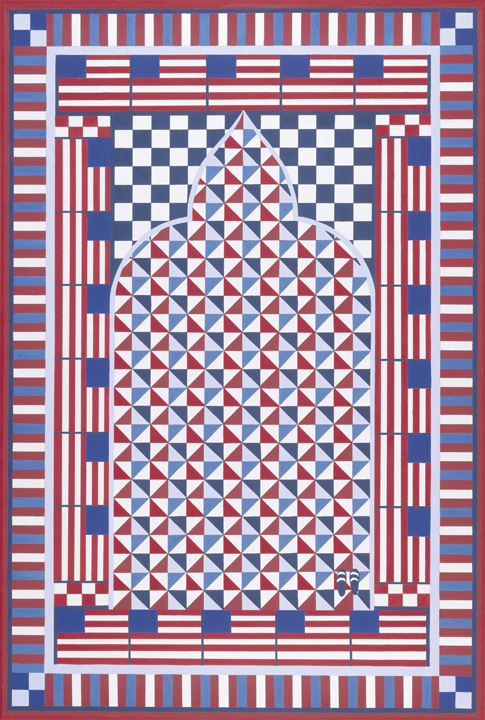

in the same show as Prayer Rug for America, by the Arab American,

Helen Zughaib. Other pieces include a photograph of the Navajo

code talkers who communicated the message to soldiers to raise

the U.S. flag at the Battle of Iwo Jima, and a mixed media work

by Chinese-American Flo Oy Wong about the detention of Chinese

immigrants at Angel Island.

There’s

a Library of Congress photograph of a young African American woman

taken in 1942. She is carefully handling flags in a quartermaster

corps depot. Again, she is unidentified; her name unknown. The

photograph challenges notions of commonly held beliefs of what

patriotism looks like. “We want to expand the historical

narrative about whom the flag represents and share the contemporary

contexts of its lived meanings,” said Dr. Michelle Joan

Wilkinson, project curator and flag art scholar. “…For

Whom It Stands aims to present diverse stories of the flag

with a wide-angle perspective in which we all can see ourselves

reflected in the national fabric.”

** Updated and reposted in 2018.

|

.jpg)